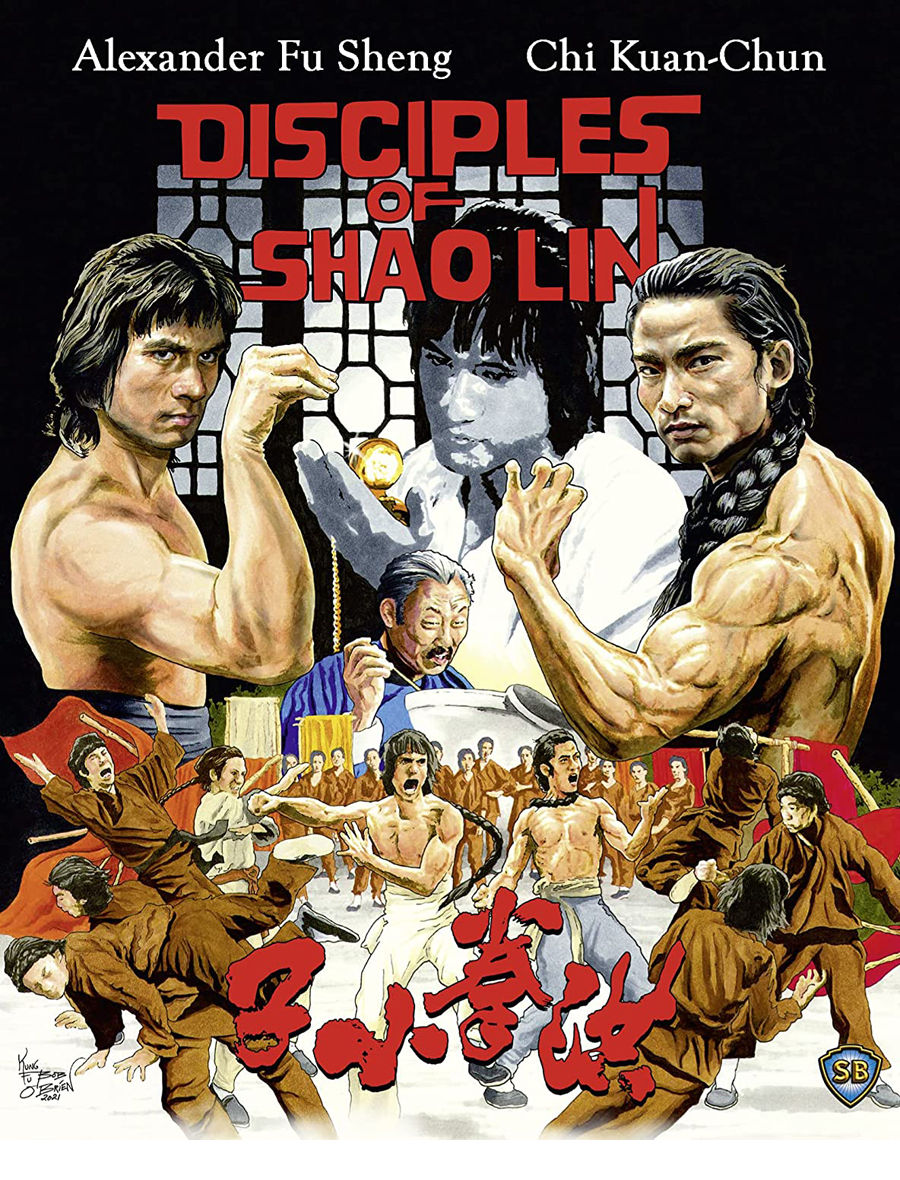

Disciples of Shaolin Blu-ray Review

- Gabe Powers

- Dec 27, 2021

- 5 min read

88 Films

Blu-ray Release: December 14, 2021

Video: 2.35:1/1080p/Color

Audio: English and Mandarin LPCM 2.0 Mono

Subtitles: English

Run Time: 107:09

Director: Chang Cheh

When shaolin disciple Kuan Fung Yi (Sheng Fu) takes a job at a textile factory, he soon becomes embroiled in a bitter and violent clash with the rival Manchu clan, who run a neighboring mill. (From 88 Film’s official synopsis)

Filmmakers like King Hu and Liu Chia-Liang set the standard for Shaw Bros. martial arts movies, but no other director had a bigger impact on the studio’s output and reputation than Chang Cheh. Chang wrote and/or directed nearly 100 films for Shaw Bros., producing enduring hits over three decades (technically four, as he made three movies in the early ‘90s), creating franchises, such as the One-Armed Swordsman series, and cultivating the team of actors known as the Venom Mob. His films were steeped in a formula now known as “heroic bloodshed,” which emphasized brotherhood, redemption, and violent sacrifice, but his style evolved with the times and helped usher in the Hong Kong New Wave styles that, in turn, took Hollywood by storm in the mid-to-late ‘90s. While he was not the first of his kind and while he borrowed heavily from other great filmmakers, Chang might still be the single most influential wuxia/kung-fu director of all time.

Disciples of Shaolin (aka: Invincible One, 1975) was released right at the center of Chang’s career, a few years before he revitalized the genre internationally with Five Deadly Venoms (aka: Five Venoms, 1978), and was co-written by frequent collaborator Ni Kuang. It was popular in China/HK at the time, but tends to be overlooked now, probably due to its proximity to big deal releases, like Heroes Two (aka: Kung Fu Invaders, 1974) and the Hammer Studios collaboration The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires (aka: The 7 Brothers Meet Dracula, 1974). It doesn’t help that it’s easy to confuse Disciples of Shaolin with Lui Chia-Liang’s Disciples Of The 36th Chamber Of Shaolin (1985), Cheung Choi-Ji’s Disciples of Shaolin Temple (1985), or Chen Ming-Hua’s King of Fists and Dollars (1979), which was released as Challenge of the Shaolin Disciples on US home video. Disciples of Shaolin hints at a sort of bridge between the operatic costume drama of the director’s earlier films and the pop-superhero antics of his post-Five Deadly Venoms releases (I say this having seen maybe a dozen of Chang’s nearly one-hundred movies, so take this as my educated guess).

Chang and Ni struggle in their attempts to combine drama and comedy throughout the narratively bulky first act and, despite short bursts of action throughout, it takes about 30 minutes to get to the first real fight scene. As such, this isn’t the best place for Shaw Bros. novices to start, especially one looking for the instant gratification of something like Five Elements Ninjas (1982). Still, the commitment to unhurried storytelling – combined with a couple story elements borrowed from Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961), sepia tone, slow motion flashbacks, some Ennio Morricone-esque musical cues, and a thematically important pair of musical pocket watches – recall the Italian westerns of the previous decade, which Chang has noted as an influence on his style. Besides, once the action picks up, it rarely lags again. Additionally, while the ideals of heroic bloodshed and brotherhood take center stage (especially after the stage is set for the violent rivalry between mills), Disciples of Shaolin’s moral outlook is also built around anti-Capitalist sentiment, which isn’t unusual (it’s more or less the subtext built into Hollywood gangster movies brought into the proper text), but still interesting, considering co-writer Ni’s reputation for anti-Communist rhetoric and fact that Hong Kong was not under Chinese Communist control at the time and, thus, not subject to state propaganda.

Video

Shaw Bros. movies have been shared via bootlegs and grey market imports for decades (remember VCDs?), so Disciples of Shaolin was seen by fans, but it appears that the only official stateside releases were a Tai Seng Entertainment VHS released in 2000 (!) and an anamorphic DVD from Image Entertainment. The first Blu-ray was a limited edition from T.V.P. in Germany (under the title Karato - Sein härtester Schlag) and 88 Films released their Blu-ray edition in the UK a couple of months prior to this North American disc. In my experience, Shaw Bros. HD transfers tend to be almost the same across the board, no matter what company is releasing them, excepting authoring issues, so I’m more or less recycling my thoughts here. The 2.35:1, 1080p transfer reproduces cinematographer Mu-To Kung’s rich, bright colors beautifully and does a good enough job filling in the busy wide-angle frames without oversharpening or moiré effects. Consistent hues and inky blacks help to neatly separate complex elements. Like most Shaw Bros. remasters, however, either DNR has been applied to the entire film or the scan itself lacked the finest detail. In motion, this is rarely an issue, but, if you look closely, you might notice the lack of grain, minor posterization, and softer textures. Also note: the mix of anamorphic lenses, varying focal lengths, and camera movement inherent in the Shaw Bros. house style leads to a lot of in-camera artifacts, such as distortion and blurriness, but these are not mastering/remastering problems.

Audio

Disciples of Shaolin comes fitted with English and Mandarin language dubs, both in DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 mono. Being a Hong Kong-based studio at a time when Hong Kong was still a British colony, most of the classic Shaw Bros. movies would have needed English, Mandarin, and Cantonese audio & subtitle options. In terms of sound quality, the two tracks are very similar, especially in terms of music and the fight scene sound effects, though the English language dub tends to overpower incidental sound, leaving it thinner than the more evenly mixed Mandarin dub. Chen Yung-Yu’s score follows the chic & funky Asian template heard from most of the era’s Shaw kung-fu movies, but puts some interesting musical twists on the formula – everything from early ‘70s American pop to Tchaikovsky and the aforementioned Ennio Morricone spaghetti western scores.

Extras

Commentary with critic and author Samm Deighan – The associate editor of Diabolique Magazine and co-host of the Daughters of Darkness podcast (with Kat Ellinger) gets right down to business with a bullet list of all the reasons Disciples of Shaolin is notable in the greater context of Chang’s work and the Shaw Bros. canon. From there, she concentrates on the thematic and structural differences between this and Chang’s other popular movies, the careers of the cast and other crew members (this was the first movie from the period that didn’t pair Chang with choreographer Lau Kar-leung, who became a director in his own right shortly after), the director’s influences, Chinese history, and the shared themes of the era’s wuxia cinema.

Commentary by Asian cinema experts Mike Leeder and Arne Venema – Leeder, who also works as casting director, stunt coordinator, and producer, and Venema, the director and co-writer (with Leeder) of the upcoming doc Neon Grindhouse: Hong Kong, discuss many of the same basic bullet points as Deighan, but from a different point-of-view. Theirs is a more energetic track, largely due to the way they’re able to bounce off of each other, and they focus a bit more on anecdotes pertaining to the filming process and personalities of the cast members.

Chang’s Disciple: Jamie Luk at Shaw Brothers (25:40, HD) – Actor/director Jamie Luk talks about his earliest experiences with the studio, the challenges of training/interning as an actor, working on Disciples of Shaolin, learning other parts of production, and making his own films with other studios.

Hong Kong trailer

The images on this page are taken from the BD and sized for the page. Larger versions can be viewed by clicking the images. Note that there will be some JPG compression.

Comments