Heisei & Millennium Era Godzilla Capsule Reviews (originally published Throughout 2014)

- Gabe Powers

- May 31, 2019

- 16 min read

What follows are my original film reviews of Sony Picture’s Heisei and Millennium era Godzilla Blu-ray releases. Most of these were randomly paired double-feature discs with mediocre A/V, superimposed English language titles, and even some English language opening credits. Basically, they were only worth owning for the movies, so I’ve opted not to include all the boring repetitive disc quality discussion. Only two Heisei movies, The Return of Godzilla (1985) and Godzilla vs. Biollante (1989), were not included in any of Sony’s collections and, as a result, they are not covered here.

Heisei period (1984–1995)

Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (Japanese: Gojira tai Kingu Gidora, 1991)

Supposedly friendly humanoids from the 23rd century have come back in time to warn mankind that a dormant Godzilla is about to reawaken and wreak havoc. The 20th century humans agree to help and head through time to kill the beast while he is still just a regular-sized dinosaur. But the mission is a ruse and the future folk have used it to trigger the rebirth King Ghidorah, an evil, flying three-headed android monster.

Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah is the direct follow-up to one of the best post-Showa films in the entire series, Godzilla vs. Biollante, and the second (of two) Godzilla movies directed by Kazuki Ōmori (following Biollante). It was also sort of a third attempt to reboot the franchise after Godzilla Returns’ attempt at recreating the original film’s moody tone and Biollante’s attempt at creating a new, stand-alone threat for Big G to fight. When both options proved to be box office failures, Ōmori and company brought back the classic Showa monsters and the multiple foe battle formula. Like all the best kaiju movies, Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah works just fine as a human-centered science fiction film first and doesn’t entirely depend on its monster fights to propel the narrative. Omori’s script recycles elements of the sci-fi-heavy Showa films and throws them in a pot with UFOs, time travelers, killer robots, a ‘manned’ half-cyborg kaiju, and a glorious scene where WWII era US forces battle a Godzillasaurus – a proto-Godzilla creature that would eventually mutate into a much larger monster following hydrogen bomb tests on its home island. Similarly convoluted plots damage other films in this collection, but Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah’s wacky excesses are consistently charming. There’s also plenty of well-executed sequences of guys in rubber suits crushing miniatures – though passing fans should note that the full-grown Ghidorah doesn’t make an appearance until about the 45-minute mark and Godzilla himself doesn’t show up for more than an hour.

Godzilla and Mothra: The Battle for Earth (Japanese: Gojira tai Mosura; aka: Godzilla vs. Mothra, 1992)

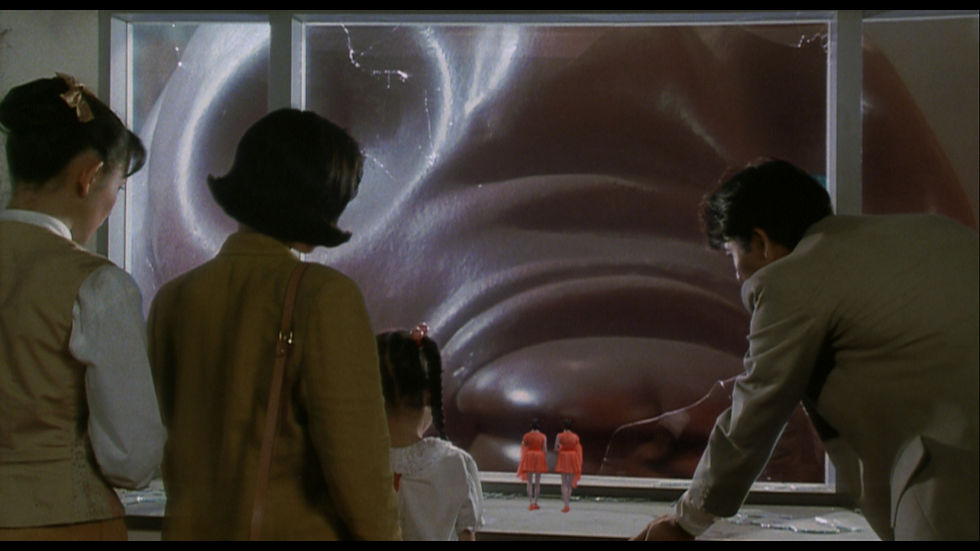

A series of devastating earthquakes unearth a gigantic egg on the mysterious Infant Island, prompting a mismatched trio of explorers and scientists to investigate. When they arrive, they quickly discover miniature twin women, the Cosmos, who inform them that the egg contains a giant monster moth named, appropriately enough, Mothra. The humans decide to ferry the egg back to the mainland – awakening a furious Godzilla, who attacks. The egg then hatches, releasing a monster larvae. Meanwhile, an evil version of Mothra, Battra (also still in a larval form) arrives to challenge the other monsters.

After scoring a substantial hit with Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah, Toho noted that their public craved new versions of classic monsters, not a darker tone or new monster threats. They wasted no time taking their second most popular kaiju, Mothra, and introducing her to the Heisei universe. Godzilla and Mothra: The Battle for Earth picks up directly where the last movie left off, but quickly establishes its own story without too many callbacks, aside from a few recurring characters. Ōmori’s script is another mashup of popular Showa-era Godzilla stories, plus bits of established Mothra mythology (…probably enough to fill an entire film on its own) and Hollywood clichés, including at least three scenes lifted from various the Indiana Jones series and a subplot about corporate goons trying to turn a profit exploiting Mothra and her little friends. Godzilla and Mothra is a more character-driven film that exchanges sci-fi themes for fantasy elements and environmental messages. Attempts at levity are usually welcome (the intended laughs far outnumber those of its predecessor) and aren’t at the expense of the stuff we’re meant to take seriously, like men in monster suits and mouse-sized fairy women. Ōmori handed over directing duties to Takao Okawara, who had been a second unit director on the series since The Return of Godzilla. Okawara is a slightly stronger technical director and has the advantage of working from a faster-paced (not necessarily better) story that digs into the monster action within the first half-hour. Godzilla and Mothra also scores points for playing Battra and Mothra’s first team-up so straight-faced that it utterly transcends the inherent wackiness of two giant rubber puppets wiggling at each other.

Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla II (Japanese: Gojira tai Mekagojira; aka: Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla, 1993)

Tired of Godzilla’s reign of terror, humanity invents Mechagodzilla – a mammoth, nuclear-powered, diamond-shielded metal robot. While construction commences, a team of scientists discover another giant egg; this time in a Rodan nest, and, because they haven’t learned anything from their previous adventures with Mothra, they bring it home for study. But the egg doesn’t house a baby Rodan – it contains a gentle baby Godzilla, whose hatching prompts a battle between the full-sized Rodan and adult Godzilla.

First-time series screenwriter Wataru Mimura’s script is a vital chapter in the ongoing Heisei series narrative. He spends the first act establishing the United Nations Godzilla Countermeasures Center (UNGCC) and their cross-continental training regiments. It’s like Philip Kaufman’s The Right Stuff (1983), only with more karate classes. This cooperative worldwide effort facilitates a more proactive place for the humans going forward. Mimura also re-imagines Mechagodzilla, once an alien weapon loosed against humanity, as a manned tool to battle Godzilla – introducing super sentai themes to the mythology and adding a bit of Power Rangers flavor that was more interesting than the endless barrage of super jets that otherwise defined the Heisei films (though, of course, one of those shows up too). Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla II also reintroduced Rodan, along with a new, less goofball Godzilla Jr. Okawara returned to direct and, armed with a more coherent script, made a tighter and more consistent film for his second outing. Some of the kaiju battles are sort of murky due to an excess of pyrotechnic effects, but Yoshinori Sekiguchi’s darker photography adds plenty of mood that doesn’t entirely override the cartoonish qualities. The title, Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla II, is an American market creation. In Japan, the film is more appropriately known as Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla. I assume the “II” was added to avoid confusion with 1974’s Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla, but this just created more confusion, especially considering that the final Showa film, Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975), was a direct sequel to the 1974 movie.

Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla (Japanese: Gojira tai SupēsuGojira, 1994)

Following the success of Mechagodzilla, Japan’s special Counter G Bureau decides to implant Godzilla with “telepathic amplifier” to control his rage. Meanwhile, the yakuza infiltrates the Bureau to wreak havoc and cells from Godzilla’s previous battles have drifted through space to a faraway galaxy where they have mutated into SpaceGodzilla, who speeds toward Earth to battle his cellular father.

Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla is one of the messiest films in the Heisei collection, but is quite grand in its ambition and thus perhaps the era’s second best (behind Godzilla vs. Biollante). It was the one and only Godzilla film directed by Kensho Yamashita, who does a fine job mimicking the house style established by Ōmori and Okawara. His human-scale scenes are dynamically shot and cinematographer Masahiro Kishimoto’s saturated photography serves the film’s cosmic themes perfectly. Despite a handful of shoddy (even by ‘90s Godzilla movie standards) digital effects shots, Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla almost certainly the most attractive entry in the Heisei series, anchored by the coolest creature design since Biollante. The novice director is joined by first-time writers, Hiroshi Kashiwabara (who later scripted Godzilla 2000) and Kanji Kashiwa. Their screenplay incorporates many elements of the previous era movies, such as the further establishment of the UNGCC and the G-Force, and includes appearances from Godzilla Jr., an improved Mechagodzilla (redubbed M.O.G.U.E.R.A. – Mobile Operations G-Force Universal Expert Robot: Aero-type), Mothra (in weird miniature form), and (briefly) the Cosmos (Mothra’s twin fairy friends). Unfortunately, Kashiwabara and Kashiwa learned very little from Mimura’s straightforward, fat-free Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla II storyline and return to the overly-busy plotting seen from Ōmori’s scripts. There are certainly some neat ideas here – especially “Project T,” a plan to hook a recurring character with psychic connections to various kaiju up to a “psychotronic” device to control Godzilla – but the overall effect is sometimes hopelessly unfocused. Still, those that are able to overlook the narrative issues and stray tone-deaf moment are in for a visual treat. It’s really too bad Yamashita’s career ended here, before he had more of a chance to cultivate his talents.

Godzilla vs. Destroyah (Japanese: Gojira tai Desutoroia, 1995)

Following his battle with SpaceGodzilla, Godzilla has become a nuclear furnace that threatens to vaporize all life on the planet. As he furiously rampages, scientists attempt to recreate the Oxygen Destroyer that stopped him back in 1994. Unfortunately, the Oxygen Destroyer has also mutated a colony of microorganisms and these new creatures, dubbed “Destroyah,” are growing at an alarming rate. Godzilla is humanity’s only hope against Destroyah, but will his meltdown commence before they can find a way to stop it?

Godzilla vs. Destroyah is a fan favourite and arguably Okawara’s finest achievement as a series director. It was also the final film in the Heisei and, for a time, was intended to be the ultimate Godzilla film. Ōmori’s script is more focused with higher stakes and plot points that tie into Ishirō Honda’s original Gojira (1954), including original black & white footage, which is cleverly used to represent memories and dreams. The dour tone sometimes overwhelms the otherwise solid human drama, but a couple of well-placed jokes and the breakneck pace minimizes the damage. The action kicks off immediately with a glowing, steaming Godzilla Prime angrily kicking his way through ancient cities. His tantrum continues, while the humans struggle with the dual task of finding solutions for the apocalyptic Godzilla meltdown and stemming the rise of mutating Precambrian organisms. Eventually, the kaiju stories converge and Destroyah makes it personal by nearly killing Godzilla Jr., giving Big G a good reason to attack, leading to one of the Heisei series’ most satisfying kaiju throw downs. The hordes of Destroyah (the most Giger-esque creatures in any Godzilla movie) and their final giant form are reminiscent of the Gyaos creatures Gamera battled in Shusuke Kaneko & Shinji Higuchi’s Gamera: Guardian of the Universe, which was released earlier in the same year. Both films features some surprisingly violent human vs. monster action as well. Okawara’s street level combat scenes demonstrate his talent for more standard-sized action and even cinematic horror. Sadly, he wouldn’t revisit either skill set ever again as a director.

Millennium period (1999–2004)

Godzilla 2000 (Japanese: Gojira Nisen: Mireniamu; aka: Godzilla 2000: Millennium, 1999)

While the The Godzilla Prediction Network (GPN) attempts to protect Japan from the creatures constant attacks, an egg-shaped UFO lands in Tokyo, baffling scientists at the Crisis Control Intelligence (CCI). Eventually, the UFO transforms into a terrifying monster, dubbed Orga, and reveals itself as a threat to the entire world. Godzilla, the GPN, the CCI, and the citizens of Japan are forced to pool their resources to battle the seemingly invincible creature.

Toho retired Godzilla for the second time when he exploded at the end of Godzilla vs. Destroyah, but left the door open for the further adventures of a younger Godzilla, who survived the catastrophe and grew to the appropriate size to wreak havoc and fight other kaiju. A few years later, Sony/TriStar and director Roland Emmerich (coming off the overwhelming success of 1996’s Independence Day) attempted to reboot the franchise for American audiences. Godzilla ‘98 wasn’t a flop, but was generally regarded as a failure. Toho, who had originally planned on holding off another Japanese Godzilla movie until Big-G’s 50th anniversary in 2004, reacted to the perceived damage to their brand by hiring Heisei era director Takao Okawara and writers Wataru Mimura & Hiroshi Kashiwabara to jumpstart a new series that was divorced from the Heisei films. Reeling from the disappointment of Emmerich’s failed experiment, Sony decided to fall back on the Hollywood tradition of re-editing and somewhat rewriting Japanese Godzilla movies for Western audiences, a tradition that began with 1956’s Godzilla, King of the Monsters and continued for Godzilla 1985. The result, Godzilla 2000, was released about one year later.

Sony’s Blu-ray release includes that shortened US release (99 minutes) and, for the first time with English subtitles, the original Japanese version (107 minutes). I was initially eager to see the Japanese cut, but was also keenly aware that a longer version of this already slow-moving and predominantly dull movie might prove problematic. In some regards, I was correct, because, in any form, Godzilla 2000 is sluggishly paced, but the longer cut does solve more problems than it creates. Okawara dives directly into the fray, skipping over excess exposition to quickly reintroduce everyone’s favorite giant lizard in all of his his man-in-suit glory. The imagery pays homage to the original film and Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (1993), and evokes a sense of mystery that had been missing throughout the Heisei era. The longer version sets up more interesting lead characters and a less campy tone, which fits the story better, but doesn’t fix the bland military led sequences. Patient viewers do have a cool climax to look forward to, however, as Godzilla’s face-off with Orga (a definitively inventive, Rancor-like monster that evolves from a UFO shape) instills a genuine sense of awe, even when hampered by ugly digital effects.

Godzilla vs. Megaguirus (Japanese: Gojira tai Megagirasu: Jī Shōmetsu Sakusen, 2000)

In a rather creative bid to rid the world of Godzilla, scientists have developed the world’s first man-made black hole. Unfortunately, during a test of their Dimension Tide device, an insect is caught in the beam and mutates. It later lays giant eggs that hatch giant dragonfly monsters dubbed “Meganula.” The Meganula feed on Godzilla’s nuclear energy, but cannot defeat him in open combat, so they create a giant queen, the Megaguirus, and set the stage for an epic monster throw down.

For years, I had regarded the Millennium films as a direct, almost indiscernible extensions of the Heisei series. After watching the series back-to-back, I’m now keenly aware of how distinct the eras really are. Sure, all of the movies still operate within the same structural confines and some changes are merely aesthetic – such as the Godzilla design and the updated special effects – but the sheer modernity of the Millennium series’ imagery (some of which includes ugly action close-ups and low frame-rate slow-motion) and the change in mood makes for a very different experience. Godzilla vs. Megaguirus was the first of three Godzilla movies directed by Masaaki Tezuka, who gets a little gritty with the material in an off-kilter attempt to emulate post-millennial Hollywood action blockbusters, while still remaining true to the franchise’s rubber suit roots. The sum effect established a mixed comedic and serious tone for much of the Millennium series, as seen in this film’s wild swings from broad comedy, to surprisingly violent horror and straight-faced action.

The previous entry was primed for a worldwide release and more eager to recognize the franchise’s camp appeal, but Tezuka set the stage for more sincere entries that were aimed at Japanese audiences and established Godzilla fans. Second-time Millennium writer Hiroshi Kashiwabara and returning Heisei writer Mimura’s screenplay is incredibly uneven, especially when it sets nostalgic callbacks to the original film alongside the grimmer hardships of regular people wrapped up in the kaiju phenomenon. The long-running franchise rule of big sci-fi ideas to counteract monster threats apply here, specifically where the black hole weapon and specialized jet are concerned, but human soldiers also begin taking on monsters with human-sized weapons. This became a fun tactic that endured throughout other Millennium films. The story’s biggest problem is that it is divided awkwardly between an somewhat boring technical plot – something that perks up when it focuses on a young member of the G-Graspers (similar to the G-Force) with a grudge against Big G named Kiriko (Misato Tanaka) – and clumsy side plots connected to the evolution of the Meganula and Megaguirus.

Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack (Japanese: Gojira, Mosura, Kingu Gidora: Daikaijū Sōkōgeki; aka: GMK, 2001)

Fifty years after they destroyed Godzilla, the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) is contending with a series of natural disasters. Among the casualties is U.S. nuclear submarine that appears to have been destroyed by the terrifying kaiju himself, who has been possessed by the souls of thousands of Japanese who died during WWII. When the military proves insufficient against Godzilla’s might, the Holy Beasts of Yamato – King Ghidorah, Mothra, and Baragon – are awakened from centuries of slumber to defend the island nation. Meanwhile, Yuri Tachibana (Chiharu Niiyama), daughter of JSDF Admiral Taizo Tachibana (Ryūdō Uzaki), and her news crew are reporting on mysterious earthquakes, when the battle to save Japan begins.

Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack is the best of the Millennium series and maybe even the best Godzilla movie since the end of the Showa era. It was directed by Shusuke Kaneko, who co-wrote the screenplay with animation veterans Keiichi Hasegawa and Masahiro Yokotani. Kaneko was hired based on the strength of his Gamera series reboot trilogy. Those films – Gamera: Guardian of the Universe (Japanese: Gamera: Daikaijū Kūchū Kessen, 1995), Gamera 2: Attack of Legion (Japanese: Gamera Tsū: Region Shūrai, 1996), and Gamera 3: Awakening of Irys (Japanese: Gamera Surī: Irisu Kakusei, 1997) – had a violent, pop-pulp edge and throwback quality that is missing from the more modernist and anime-infused Millennium movies. Kaneko brought this no-holds-barred mean streak to Giant Monsters All-Out Attack, skirting the line between kid-friendly and exploitative violence.

Giant Monsters All-Out Attack’s greatest strength lies in the way it streamlines and reinvents the series’ most basic and repeated conventions. Besides using a very different, some might say dated Godzilla design when compared to the other Millennium films (which otherwise feature a slimmer, more flat-headed creature costume), the Kaneko returns Godzilla to his vengeful villain roots, minus even the small hint of redemptive behavior seen throughout the post-Showa movies. However, Giant Monsters All-Out Attack really bucks trends by portraying all the other monsters, (including King Ghidorah, who is given a new, Earth-based back-story), as the human-saving heroes trying to stop Big-G’s destructive rampage. Those of us willing to embrace the change (I’ll admit that I was initially too married to the concept of reluctant hero Godzilla to fully enjoy GMK the first time I saw it) are in for a treat with this particularly action-packed, thoughtful, fast-moving, and darkly comedic film (the grisly highlight being that King Ghidorah is accidentally discovered by a salaryman attempting to hang himself in Aokigahara, aka: the Suicide Forest).

Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla (Japanese: Gojira x Mekagojira, 2002)

Despite killing the original Godzilla in 1954, Japan Self-Defense Forces are still battling his species. When their original weapons prove useless, the JSDF creates a cadre of new ones, including a supersized fighter jet, an ice laser called the Absolute Zero Cannon, and a biomechanoid Mechagodzilla crafted from Godzilla’s own bones, codenamed Kiryu. A formally disgraced canon tech named Akane Yashiro (Yumiko Shaku) is transferred to a position as Kiryu’s main pilot, to the chagrin of some of her comrades. But bigger challenges arise when Godzilla’s presence awakens Kiryu’s monstrous instincts.

Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla saw the return of Godzilla vs. Megaguirus (2000) director Masaaki Tezuka, who vastly improved as a filmmaker between the two films (and who would improve again with Tokyo S.O.S.). Both the Millennium Mechagodzilla movies represent a shift back towards sentai and giant robot anime imagery, something that would be carried through to the rest of the series, even while continuity was severed. The Millennium movies handled this stuff better than the Heisei series, in large part because Tezuka figured out how to capture the necessary kinetic energy. Returning Giant Monsters All-Out Attack writer Masahiro Yokotani and Godzilla 2000 writer Wataru Mimura continue recycling basic plot elements from the Showa, including nods to non-Godzilla Toho movies, like Ishirō Honda’s War of the Gargantuas (Japanese: Furankenshutain no Kaijū: Sanda tai Gaira, 1966; itself a sequel to Honda’s Frankenstein Conquers the World, 1965), and Honda’s Space Amoeba (Japanese: Gezora, Ganime, Kamēba: Kessen! Nankai no Daikaijū, 1970). The screenplay can be overly sentimental and trip over intersecting ideas, but moves along quickly and the cast is likeable, especially Yumiko Shaku, who returned for the next movie...

Godzilla: Tokyo S.O.S. (Japanese: Gojira x Mosura x Mekagojira Tōkyō Esu Ō Esu; aka: Godzilla × Mothra × Mechagodzilla: Tokyo SOS, 2003)

Mechagodzilla/Kiryu is undergoing repairs following a devastating battle when Mothra’s twin heralds appear to warn the Japan Self-Defense Forces scientists that their reconstruction will lead to dire consequences. Sure enough, Godzilla is awakened, attacks Tokyo, and an unfinished Kiryu is put back into service. Later, Mothra and her larvae join the fight.

As mentioned, Godzilla: Tokyo S.O.S. was the only direct sequel in the Millennium collection. Giant Monsters All-Out Attack writer Masahiro Yokotani and director Tezuka himself (in his only credited writing gig) took over screenplay duties from Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla writer Mimura. Like its predecessor, Tokyo S.O.S. returns to the good ol’ generic Godzilla plot well and references shots from the Showa era Toho series (including the Godzilla movies, the Mothra movies, and the Gargantua/Frankenstein series). The screenplay occasionally feels repetitive and overly contemplative (especially when you watch a bunch of these movies in a row), but not nearly as convoluted as some of the drier Heisei entries. As an overall achievement, Tokyo S.O.S. is probably Tezuka’s masterpiece. It shows significant improvement and technical polish over Megaguirus and even Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla, highlighted by hyperactive action and earnest, but not maudlin character interactions. The pacing is still too leisurely, but the tonal shifts don’t buck up against each other. It’s a sincere Godzilla movie that doesn’t take itself so seriously that the audience can’t have fun with it.

Godzilla: Final Wars (Japanese: Gojira: Fainaru Wōzu, 2004)

Long ago, Godzilla was successfully buried deep beneath the ice in the South Pole, never to be heard from again. Then, after years of peace, other kaiju returned to wreak havoc worldwide. When all seems lost, a massive U.F.O. suddenly appears and neutralizes all the monsters with a mysterious laser beam. The aliens, dubbed “Xiliens,” announce that they have come in peace, but it isn’t long before their insidious plans to conquer the planet are revealed. Unable to battle the Xiliens’ legions of giant creatures, Earth forces begrudgingly free Godzilla from his icy prison in hopes that he will retake the Earth.

Following modest, though consistent box office popularity, the original Gojira’s 50th anniversary rolled around and Toho Pictures decided it was time to once again retire their biggest cash cow (physically speaking), at least for a while. Instead of returning to one of the Heisei or Millennium era’s repeat filmmakers, they opted to take a big chance on hip action director Ryuhei Kitamura, who had blazed a meteoric trail from low-budget zombie-yakuza epic Versus (2000), through celebrated manga adaptation Azumi (2003) and Sky High (2003). Kitamura’s M.O. was (and has somewhat remained) that of an “elevated junk food salesman.” His movies were (and are) fun, flashy, pop machines with little thematic meat on the bone. The lack of substance is rarely an issue, but what continues to plague his career is his lack of editing. All of his films are too long and too packed with fan-service. The aptly titled Godzilla: Final Wars is no exception, though the director was clear from the beginning that he intended to combine his favorite aspects of all of the Showa era movies and a record number of kaiju opponents for Godzilla to take on. Unable to keep his homage or animation/comic book-inspired impulses at bay, Kitamura made an all-you-can-eat buffet designed to make fans and detractors alike sick. Still, it’s not a bad film – to the contrary, it’s complete break from the aesthetic monotony of the previous two decades is refreshing and its almost desperate attempts to ape quickly fading Hollywood trends (like Matrix-inspired PVC costumes and Nu Metal soundtracks) are quite charming a decade-plus after its release. Mimura did return again as writer, along with Isao Kiriyama, and the plot is based on Honda’s 1965 Showa era classic Invasion of Astro-Monster (Japanese: Kaijū Daisensō), but this is really Kitamura’s baby, for better or worse.

Decades of manufacturing later, we still find the best telescope eyepiece brands not being able to deliver excellent magnification and detailed pictures. Prospect astronomers have thus resorted to external equipment such as telescope eyepiece.